Contents

- Introduction

- Preface

- Overview

- Relief Valve

- LECTURE 1: Why We Are In The Dark About Money

-

LECTURE 2: The Con

- The Banker Explained - The Wizard of Oz

- Why Do We Need Banks?

- What Bank Supervision?

- Banks Too Big To Fail

- Banks Cheat

- Banks and Money Laundering

- Banks Sell Drugs

- Money is NOT the same as Currency

- Currency Markets Are Rigged

- HFT High Finance Trading Predators

- Libor

- London Gold Fix Proof of Bank Manipulation

- QE Quantitative Easing

- A Trust Deficit Caused by Predator Bankers' Secrets

- HSBC The Pirate Bank

- HSBC The Dirtiest Bank

- Propaganda

- Banks Role in Terrorism

- The Octopus

- The First Banks in America

- History of Banking – Index (by date)

- Wealth Distribution and Why do the Rich Get Richer?

- Learn How Lobbyists Buy Politicians

- Commerce Without Conscience

- The Shattered American Dream

- United States Treasury Department

- About Gold and Fort Knox

- Paying Taxes in April

- Lecture 2 Objectives and Discussion Questions

- LECTURE 3: The Vatican-Central to the Origins of Money & Power

- LECTURE 4: London The Corporation Origins of Opium Drug Smuggling

- LECTURE 5: U.S. Pirates, Boston Brahmins Opium Drug Smugglers

- LECTURE 6: The Shady Origins Of The Federal Reserve

- LECTURE 7: How The Rich Protect Their Money

- LECTURE 8: How To Protect Your Money From The 1% Predators

- LECTURE 9: Final Thoughts

The Continuation of the Jardine Family Story of Banking and Drug Smuggling

WILLIAM JARDINE

IRON HEADED

OLD RAT

On 5 September 1832, after a six-month voyage The Lord Amherst returned to Macau, a Portuguese settlement at the mouth of the Pearl River estuary below Guangzhou. All of the Western merchants were required to stay there, except during the trading season of November through March. [pdf]

No one treated the news from the expedition with greater interest than a 40-year-old doctor turned trader called William Jardine. Single-mindedly pursuing the creation of a fortune, which would eventually enable him to return to Great Britain in baronial style, Jardine was a shrewd and determined merchant. To ensure that visitors kept to the point, his office only contained one chair, for himself. His Chinese nickname seemed appropriate. They called him the “Iron Headed Old Rat”.

Jardine saw considerable value in the commercial intelligence brought back by Lindsay and his party. To exploit the opportunities, however, he needed the assistance of Gutzlaff, both as guide and as interpreter. Obtaining the services of a missionary may be difficult, however, Jardine sold opium.

Jardine saw considerable value in the commercial intelligence brought back by Lindsay and his party. To exploit the opportunities, however, he needed the assistance of Gutzlaff, both as guide and as interpreter. Obtaining the services of a missionary may be difficult, however, Jardine sold opium.

With his partner, James Matheson  a fellow Scot 12 years his junior – and like himself a second son, who had to make his own way in the world – Jardine had become one of the major suppliers of opium to China. The narcotic was a key link in the triangular British-controlled trade by which tea was shipped from China to England, paid for by opium shipped from India to China, which in turn paid for exports from England to India.

a fellow Scot 12 years his junior – and like himself a second son, who had to make his own way in the world – Jardine had become one of the major suppliers of opium to China. The narcotic was a key link in the triangular British-controlled trade by which tea was shipped from China to England, paid for by opium shipped from India to China, which in turn paid for exports from England to India.

Opium formed a significant part of the revenues of the East India Company, known in Asia as “The Honourable Company”, at the time without irony. The company controlled the production of opium in Bengal and organized annual auctions at Calcutta.

Because the consumption of opium was illegal in China, the Honourable Company did not handle it directly.

Doing so could jeopardize its enormously profitable monopoly on the tea trade between Guangzhou and England. Accordingly, it felt obliged to maintain that surface propriety so beloved by both Chinese mandarins and the English upper classes. Even in his covert mission pretending to be a trader, but in fact representing the East India Company, Lindsay had not carried any opium on board, to the surprise of many Chinese he met.

The company’s abstention from the distribution end of the market created an opening for merchant adventurers like Jardine and Matheson. They could act as commission agents for the Indian traders, who bought the drug at the Calcutta auctions, exporting it to China with the encouragement of the Honourable Company, which intended to buy their silver proceeds from opium sales with negotiable bills of exchange payable in London.

Jardine had come to Asia 20 years before as a surgeon in the employ of the Company. At that time only 2,000 chests of opium were exported to China, most of it Patna and Benares opium from Bengal. The distinctive packaging and trademark used by the East India Company had become a hallmark of quality for Chinese consumers. Each clearly recognizable mango wood chest comprised 40 compartments arranged in two layers, every compartment containing a trademarked three pound spherical cake of opium, protected by an inch thick layer of poppy leaves.

The Honourable Company had displayed a fitting concern for the promotion of its illegal product. “We had opium sent to us in small quantities”, Jardine would later reveal, “packed in different ways, with a request that we would sell it and ascertain the kind of package that suited the Chinese market best”.

The Honourable Company had displayed a fitting concern for the promotion of its illegal product. “We had opium sent to us in small quantities”, Jardine would later reveal, “packed in different ways, with a request that we would sell it and ascertain the kind of package that suited the Chinese market best”.

At first the trade grew slowly, reaching 4,000 cases in 1820. Then it erupted, tripling within the decade and tripling again in the next. The new supplies included a considerable quantity of Malwa opium from the western Indian states, not yet controlled by the East India Company. Although regarded as inferior in quality, Malwa opium did compete in price. Independent traders sought access to production beyond the strict quotas monopolistically imposed by the East India Company in Bengal. When Jardine returned to Guangzhou to stay in 1822, he came as the agent of Parsi traders from Bombay who dealt in Malwa opium.

The Parsis of Bombay, abiding by the faith of the monotheistic Persian prophet Zoroaster, were refugees from Muslim persecution in Iraq and Iran. They had prospered in the comparative religious freedom of Company controlled Bombay. By successfully avoiding the efforts of the Honourable Company to restrict exports from Bombay, and therefore limit independent production in the western states, the Parsis caused an explosion in the availability of opium in China. They were the owners of the opium which was distributed on a commission basis by partnerships like Jardine Matheson and Co. The risk of piracy and price collapse was borne by the owners. As Jardine put it, “the opium commission business was by far the safest trade in China”.

The marketing of opium turned on a range of commercial considerations about which up-to-date intelligence was essential. Information was required about the full range of factors that could affect supply and demand: crop conditions in India, the latest auction results, the level of stocks held by rival traders, the timing and intensity of the periodic attempts by Chinese officials to suppress the trade. Agents like Jardine and Matheson controlled the final wholesale distribution point. That required the maintenance of fully armed ships and the systematic bribery of Chinese officials, designed not just to permit Jardine Matheson to trade but also to interfere with the activities of their rivals.

In 1830 Jardine, when encouraging a friend to invest in opium, asserted: “Opium is the safest most gentleman like speculation I am aware of”. Jardine later exclaimed at a dinner of Guangzhou traders, “We are not smugglers gentlemen! It is the Chinese government, it is the Chinese officers who smuggle and who connive at and encourage smuggling, not we”.

English law at that time prescribed that a national boundary did not extend beyond the high watermark. The three-mile limit rule came later. Jardine was satisfied that it was impossible to “smuggle” in international waters. If the Chinese had a different rule, or even a rule similar to the principle of accessory before the fact of the English criminal law, that would not justify calling someone a “smuggler” in English.

Jardine was much concerned with his status as a gentleman, and with reason. A growing body of opinion in England regarded the narcotics trade with distaste. He did not wish to return to Great Britain with a fortune, only to be shunned by British society. Nevertheless, he and other Britons, notably Scottish, together with a few Americans and significant number of Indians, more often than not of middle eastern extraction, particularly Parsis and, later, Jews, were the Colombian drug barons of their day. They founded a number of family fortunes and major corporations which are still of great significance.

Opium would remain legal in England until the first Pharmacy Act in 1868. Notwithstanding its literary glorification, by Thomas De Quincy and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the main use of opium in England was as an infant quietener for the phalanx of harassed English nannies. Druggists sold large quantities of opium-based elixirs under such brands as “Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup” and “Godfrey’s Cordial”, especially to the baby-minders employed by working mothers.

The British and American traders were wholesalers, rather than retailers. They sold to Chinese merchants who visited the heavily armed opium store ships situated, with the connivance of the bribed local Chinese mandarins, off Lingding Island near Macau. There were fortunes to be made, which could be laundered through East India Company bills of exchange.

Matheson had attempted to create a direct coastal trade some years before. The reports brought back by Lindsay and Gutzlaff indicated that the time had arrived to try again. Indeed, it was on 1 July 1832, while The Lord Amherst was actually in Shanghai, that the trading house of Jardine Matheson & Co, destined to be the most enduring firm on the China coast, was formally established under the name which continues to this day. Its first major enterprise as such, in the wake of the return of The Lord Amherst, was to dispatch a ship full of opium to trade along the coast, including at Shanghai.

On such a journey, the traders could not rely on the gibberish pigeon English in which staccato negotiations were haltingly conducted in Guangzhou and on Lingding. Few westerners had had the determination or the motivation to flaunt the Imperial ban on the teaching of Chinese to foreigners. Only one – Karl Gutzlaff – had managed to master the dialects of a number of different provinces, whose languages were as closely related, but also as mutually incomprehensible, as French, Italian and Spanish.

A pioneer of the contemporary Protestant religious revival, which emphasised the value of evangelical preaching of the Gospel with the Scripture as the only basis for a personal faith, Gutzlaff had a motive for understanding the Chinese people which no merchant could share. Unlike the merchants, he and his fellow missionaries had come to help the Chinese, rather than themselves.

“My love for China is inexpressible”, he wrote to a friend, “I am burning for their salvation. I intercede for hundreds of millions which do not know the Gospel, before the throne of grace”. Gutzlaff was never short on hyperbole.

“I would give a thousand dollars”, one English trader wistfully stated “for three days of Gutzlaff”. Jardine and Matheson were willing to pay what it took.

In the previous year, the monopolistic East India Company, acting in retaliation for the new competition from West Coast opium which it did not control, had doubled production in its Bengal region. An oversupply threatened and, accordingly, new markets had to be found.

Jardine, no doubt, stifling his irritation with Gutzlaff’s aura of Teutonic omniscience and his evangelical fervour, which he probably regarded as humbug, approached Gutzlaff with care.

“It is our earnest wish that you should not in any way injure the grand object you have in view by appearing interested in what many consider an immoral traffic”, he wrote engagingly. “Yet such traffic” he continued, “is so absolutely necessary to give any vessel a reasonable chance of defraying her expenses that we trust you will have no objection to interpret on every occasion when your services may be requested”.

Of course Jardine also offered to support the propagation of the faith by underwriting Gutzlaff’s Chinese language magazine for six months. He added a further incentive:

“The more profitable the expedition, the better we should be able to place at your disposal a sum that may hereafter be employed in furthering your mission and for your success, in which we feel deeply interested.”

Gutzlaff had lost his original sponsorship from the Netherlands Missionary Society, when he decided to work in China, too far afield from the Dutch colonial sphere of interest in the East Indies. He had supported his mission on the inheritance from the first of his three English wives, but that would not last indefinitely. He needed the money.

Gutzlaff had experienced the ravages of opium at first hand. Dressed in Chinese garb, he had once traveled along the coast in a Chinese junk. At times on the voyage he was the only person aboard who was not stupefied by the drug. He had no illusions about the effect of opium on addicts as it ruined their digestion, sallowed their complexion, separated their gums, blackened their teeth, rotted their minds and induced constant trembling. These were the souls he had come to save. God, however, works in mysterious ways.

A zealot like Gutzlaff, who had studied medicine in order to better equip himself for his mission, can convince himself of just about anything. In his published memoir, recording how he accepted the Jardine offer, he said: “After much consultation with others and a conflict in my own mind, I embarked on The Sylph”.

The Sylph was one of the first opium clippers, specifically designed for, and dramatically increasing the productivity of, the opium trade. A barque rigged, square-sterned vessel of 300 tonnes, The Sylph had been designed in London by Sir Robert Sebbings, then surveyor of the Royal Navy, to the order of a consortium of Calcutta merchants. Sleek, elegant, functional and devoid of ornament, The Sylph did not have the rakish lines of the later clippers, yet it proved to be particular swift.

The so-called “country trade” in opium between India and China had hitherto been conducted in the slow, corpulent, “country wallahs”, constructed of Malabar teak in the shipyards of Bombay and on the Hooghly River near Calcutta. The wallahs were generally mere replicas of caravels, carracks and even galleons, with a projecting bow, a high narrow roundhouse at the stern, heavily leaded windows in gilded, sumptuously carved quarter galleries, with intricately carved cannons poking out from ports surrounded by gilt carvings.

The lack of commercial urgency associated with the East India Company’s monopolistic routines had established this wasteful model. The country wallahs, like the equally cumbersome old East India frigates that carried tea, could only make one round trip to China per year. These ships could not sail into the monsoon, which dominates the China Sea between October and March. They generally took two or three months between India and Lingding Island, proceeding gently before the southwest summer monsoon, returning with the assistance of the stronger northeast monsoon of winter.

For the whole of maritime history size and speed had been inversely related. Large vessels designed to carry bulky cargoes were slow. The clippers were the first major attempt to reproduce the lines of speed in a large vessel. They were modelled on American privateers, built to avoid the trade restrictions imposed by Britain on the American colonies. This was smuggling in the grand manner, with private enterprise driving technological improvement and increased productivity.

Speed was the essence of commercial success in this trade. It reduced the transport costs per case of opium. The clippers would take less than three weeks, instead of three months, and could, by sailing into the monsoon, do three round trips a year. Speed also gave the trader a head start: he received the latest commercial intelligence and supplies from the annual crop could arrive in advance of rivals, with additional flexibility to direct them in the most lucrative way.

The Sylph had just arrived on its maiden voyage from India on 1 September 1832 in a record 18 days, just a few days before the return of The Lord Amherst. On 20 October with a 70 man fully armed crew, it set sail from Macau into what Gutzlaff later described as “furious gales and a tremendous sea”. Its main cargo was opium.

After sailing as far north as Manchuria, The Sylph returned to the mouth of the Yangzi in mid December. In high seas it saved the crew of a demasted junk. “The first thing which they handed to us”, Gutzlaff recalled with disgust, “was an image of the Queen of Heaven”. Piously rejecting what he called a “heathenish delusion”, Gutzlaff bellowed “Let the idol perish”, which it did by being thrown overboard. Nevertheless, saving the crew stood The Sylph’s party in good stead during their two-week stopover near Shanghai.

Gutzlaff’s memoir recalls with pride the urgent demand for the religious tracts he had brought in such large number on his return to the city. Gutzlaff boasted “Most joyfully did they receive the tiding of salvation”. He failed to mention to his British readers the fact that the extraordinary Chinese respect for learning led the population to treasure all writing, irrespective of its content. This was not a reaction that his contemporary British audience would naturally understand.

Gutzlaff’s memoir is silent on the opium sales for which he acted as an interpreter. The work must have been quite intensive at times. A Jardine Matheson captain recorded in his journal for another voyage: “Dr Gutzlaff distributing religious tracts from one side of the vessel, at the very time that opium was being delivered over the other side”. Another captain wistfully recorded: “Employed delivering briskly, no time to read my Bible”.

The opium trade was conducted at Wusong, where the Huangpu entered the Yangzi, a convenient distance from Shanghai and just out of sight of official recognition. As a Western treaty port, the opium barges would be hypocritically parked there for the best part of a century.

The captain of The Sylph, unlike Lindsay, accepted the offer of free provisions from the Shanghai mandarins. This was after all a purely commercial venture. And a staggeringly successful one. Six months after its departure The Sylph returned to Lingding Island and disgorged $250,000 of silver into the Jardine Matheson and Co receiving ship.

The future was also assured. The number of new addicts probably numbered in the thousands. Opium was the perfect consumer commodity. The very act of consumption created demand for more.

THE LORD AMHERST

During the visit of The Lord Amherst, John Rees, captain of the ship, prepared detailed charts of the navigable approaches to Shanghai by following the Chinese junks and by taking detailed soundings. He carefully recorded his route and named certain features – Amherst Passage, Gutzlaff Island – as if for the first time, without inquiry about any existing name. These were the first accurate European maps of the area. They would be of crucial significance for future smugglers and traders, as they were for The Sylph. Within a decade they would also direct a British military expedition to the walls of Shanghai, which fell without resistance on 19 June 1842, ten years less one day after Lindsay had ordered his sailors to force entry to the Daotai’s yamen.

When the ships arrived, their cannon first destroyed the forts of Wusong. Amongst the hundreds of ineffective brass cannon they captured, one was pretentiously engraved “Tamer and Subduer of Barbarians”.

About 250 years before, Xu Guangqi had successfully introduced cannon cast in the Western manner to Ming military equipment. He and other converts had also applied Euclidean geometry, adopting the idea of ballistics as a science. In astronomy, the Jesuit influence had continued in China, but in military science it had long been forgotten. The idea that a trajectory of a cannon ball could be plotted had been lost.

Without an understanding of Euclid, China could not understand the West or the threat it posed. When the Western cannon subjugated the fortifications at Wusong in 1842, Euclid had returned to Shanghai.

BANKS SELL DRUGS

Henry Keswick: Chairman of Jardine Matheson, once known as one of the largest opium-smuggling companies of the world.

According to EIR, they are still involved in this type of business today. His brother, John Keswick, a backer of the WWF, is chairman of Hambros Bank (Peter Hambro is a member of the Pilgrims Society) and a director of the Bank of England.

The Keswick family controls Jardine Matheson.

Formerly known as Hong Kong Shanghai Bank Corporation, HSBC has served as the world‟s #1 drug money laundry since its inception as a repository for British Crown opium proceeds accrued during the Chinese Opium Wars.

ONLINE PHARMACY SITES

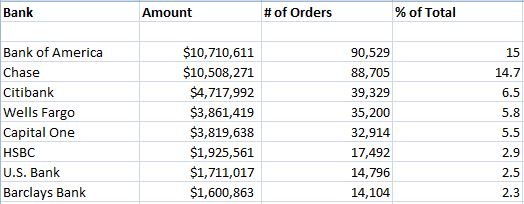

More than half of all sales at the world's largest rogue Internet pharmacies in the last four years were charged to credit and debit cards issued by the top seven card-issuing banks.

Banks make money from online pharmacy sites that sell a variety of prescription drugs without requiring a prescription.

Policymakers could stop online drug sales by legislating card-issuing banks to stop accepting these charges.

The spam ecosystem could be crippled if banks stopped processing payments to a handful of institutions. Technically, if [card-issuing] banks were willing to adopt a blacklisting approach, there is absolutely no way these pharma outfits could keep up.”

The Glavmed sales using cards issued by the top seven credit card issuers were almost certainly higher than listed in the chart above. About 12 percent of the Glavmed sales could not be categorized by bank ID number (some card issuers may have been absorbed into larger banks). Hence, the analysis considers only the 88 percent of Glavmed transactions for which the issuing bank was known. More significantly, the figures in this the analysis do not include close to $100 million in sales generated during that same time period by Spamit.com, a now defunct sister program of Glavmed whose members mainly promoted rogue pharmacies via junk e-mail; the leaked database did not contain credit or debit card numbers for those purchase records.

Researchers discovered that 95 percent of the credit card transactions for the spam-advertised drugs and herbal remedies they bought were handled by three financial companies — based in Azerbaijan, Denmark and Nevis West Indies. The full paper is available here (PDF).

15% OF ALL GLAVMED PURCHASES (APPROXIMATELY $10.7 MILLION IN ROGUE PILL BUYS) WERE MADE WITH CARDS ISSUED BY BANK OF AMERICA.

KrebsOnSecurity got a copy of Sales data stolen from Glavmed, a Russian affiliate program that pays webmasters to host and promote internet pharmacys. The Glavmed database, includes credit card numbers and associated buyer information for nearly $70 million worth of sales at Glavmed sites between 2006 and 2010.

I sorted the buyer data by bank identification number (BIN), indicated by the first six digits in each credit or debit card number. My analysis shows that at least 15% of all Glavmed purchases (approximately $10.7 million in rogue pill buys) were made with cards issued by Bank of America.

I asked Igor Gusev, the founder of Glavmed. Gusev is a fugitive from his native Russia, which last year lodged criminal charges against him and his business. In a phone interview with KrebsOnSecurity, Gusev said putting more concerted pressure on the merchant banks would decimate the rogue pharmacy industry, which tends to coalesce around a handful of processors and switch processors in lockstep when forced to move. For example, since the University of California study was published, the pharmacies featured in the study that were processing at Azerigazbank (AG Bank) in Azerbaijan stopped using AG Bank and moved their business to another institution in that country — Bank Standard.

“They need to put pressure on the card processors which are monsters [that] only regulate on very negative public pressure,” Gusev said. “I think it would be a very powerful strike, and online pharma would be dead within two years if they could somehow switch off the merchants who [are] connected to online pharma.”