Contents

- Introduction

- Preface

- Overview

- Relief Valve

- LECTURE 1: Why We Are In The Dark About Money

- LECTURE 2: The Con

- LECTURE 3: The Vatican-Central to the Origins of Money & Power

- LECTURE 4: London The Corporation Origins of Opium Drug Smuggling

-

LECTURE 5: U.S. Pirates, Boston Brahmins Opium Drug Smugglers

-

THE BOSTON BRAHMINS

- Clipper Ships

- The Boston Money Tree

- John Perkins Cushing

- Abiel Abbott Low

- William H. Russell and Samuel Russell

- The Combination Russell, Jardine, and Matheson

- Russell Sturgis

- Colonel Thomas Handasyd Perkins

- The Perkins Family

- Frances Perkins--The Only Good Brahmin

- American House of Russell and Co.

- Harvard Corporation

- Opium to Brahmins to Yale to CIA

- Forbes Family I

- Warren Delano

- Hope & Co. - Baring Brothers Bank

- John Jacob Astor

- Taft Family

- 1924 America's 1% Exposed

- Proof FDR Knew About his Grandfather's connection with Opium China Trade

- Forbes - John Kerry Family II

- George Bush Family Origins in Opium Drug Smuggling

- Black Market Bones

- Thuggee Barbara Bush Family

- Thuggee Bush Family and the CIA

- John Quincy Adams and the Chinese Opium Trade

- The Ammidons

- Augustine Heard

- Joseph Coolidge IV

- Lowell Family

- Pirates Profiteers Banksters Traders Transfers

- Pirates

- White Slavers, Cargo, Property, Auctions, Amazing Grace

- $ Colonial Labor: Indentured Servants

- England to Philadelphia Slave Trade and Opium

- Extract from Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions to Patroons 1629

- The Definitive Treaty of Peace

- Pennsylvania Charter of Privileges 28 October 1701

- Opium Trade -- American Drug Smuggling Pirates

- Opium In America

- 1% Power Elite Networks

- 1% Elite Networks Bush & The CIA

- BEFORE Skull & Bones

- SKULL AND BONES

- Caribbean Pirates in the American South

- Who Were the Tories

- The Golden Age of Imperialism Opium Act 1908

- Global Dominance Groups

- The New World Order

- Characteristics of Fascism

- War on drugs

- Lecture 5 Objectives and Discussion Questions

-

THE BOSTON BRAHMINS

- LECTURE 6: The Shady Origins Of The Federal Reserve

- LECTURE 7: How The Rich Protect Their Money

- LECTURE 8: How To Protect Your Money From The 1% Predators

- LECTURE 9: Final Thoughts

The Era of the Clipper Ships Maritime Links

2016 London is now the global money-laundering centre for the drug trade,

says crime expert Gomorrah author Roberto Saviano says 'the British treat it as not their problem'

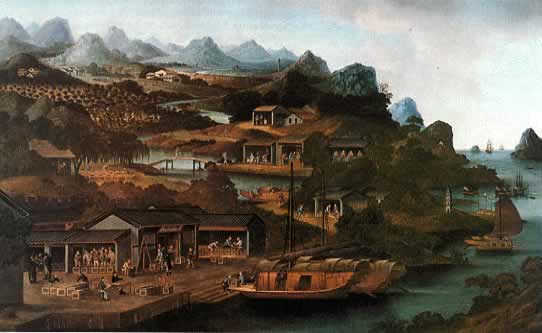

In 1842, the Opium War came to a end after the signing of the Treaty of Nanking. England now had control of the island of Hong Kong and from this base of operations, opium smuggling grew with each passing year. Sleek new opium clippers were now being built for this highly profitable trade, many of them in Aberdeen, Scotland.

The early opium clipper Red Rover

American merchants, eager to take advantage of this new opening of China, began negotiations with Chinese officials for access to additional mainland ports besides Canton. Shanghai, Ninghsien, Amoy, and Foochow were opened up to American trade. With this opening, came a growing sophistication amongst Americans for the many subtle exotic varieties of tea such as Lumking, Hyson, Imperial, Gunpowder, Bohea, and Mowfoong. The freshest teas commanded the premium prices; the lion’s share of which went to the shipping companies that could deliver the highly perishable crop to New York and Boston in the shortest possible time. The first tea-laden ship to arrive at South Street with the new year's crop would fetch the premium price at auction.

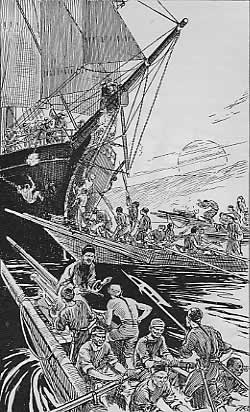

Chinese Attack on an Opium Clipper

As this market grew following the Opium War, shrewd shippers realized the growing importance of acquiring large fast ships with which to go up against their rivals in this increasingly competitive trade, and to dispatch their ships to Chinese ports every autumn to await the first tea pickings.

Once the tea was in the holds, the great sailing race half way around the world commenced down the South China Sea, past Anjier, across the Indian Ocean, around the Cape of Good Hope, and up the Atlantic to New York.

The Low brothers were early on the scene in China. They were all sons of Seth Low, a drug merchant of Salem who had a dozen sons. Seth Low saw his opportunity as early as 1833, and had made his fortune in the China tea trade and importing such exotic wares as mocha, asafetida, gum arabic, and musk in pods. Like many of the Yankee merchants, the Lows had moved from Salem to New York City, finding it a much more suitable location from which to conduct their business. They were such a numerous clan that someone from Salem, in jest, made up a jingle about them: "Old Low, old Low's son, Never saw so many Lows since the world begun."

Abiel Abbott Low had been in Canton for seven years serving with the merchant firm of Russell & Company. One Low brother after another followed him to Canton to work for the same firm. Abbott had made his fortune by 1840 and returned to New York the following year and continued to conduct his business in New York and established the family firm of A. A. Low & Bros.

Captain Nat Palmer and the Paul Jones arrived in the Portuguese colony of Macao in 1843. All along the way, Captain Nat had been putting the Paul Jones through her paces; testing her to see what she could do in the Indian and southern Pacific oceans; trying to figure out just how her design could be improved. At Macao, he took on as passengers William Low and his pregnant wife, Ann, for the passage back to New York. William Low had been the A. A. Low & Bros. representative in Canton for a while and now they were returning home so that Ann could have her baby there.

On the first part of the passage home, Captain Nat sailed against the monsoon. It was slow going; tacking back and forth as the Paul Jones clawed her way against the monsoon across the South China Sea. But even worse as far as Captain Nat was concerned, was no wind at all. He would come on deck, fly into a rage, and take off his old white beaver hat and stomp on it; screaming "Damn the calm and everything else."

Eventually Captain Nat cooled down and to vent his frustration began carving a block of wood into the shape of what he thought the ideal hull of a Canton trader should look like, one that Captain Nat thought "would outsail anything afloat." He incorporated John W. Griffiths' ideas concerning a sharp concave bow with his own ideas of a fuller flat-bottomed hull.

William Low began to take a lively interest as he watched Palmer whittling away at the model. He well understood Captain Nat's frustrations and the two had the opportunity to talk ship in the evenings after dinner over brandy and cigars, as the model slowly took shape over the coming days. William Low was soon intrigued and the new idea of just what an ideal China Clipper hull should look like swiftly became one of mutual interest as Low suggested that his firm might be interested in building such a vessel. Captain Nat was well pleased that he would at last get the opportunity to design a China tea clipper that could sail through the calms and give his old white beaver hat a rest.

Soon after the voyage ended at the South Street wharf, Captain Nat and his model accompanied William Low and his wife to the A. A. Low & Bros. building at 167-171 John Street to meet with Abiel Low, the head of the firm who had spent many years in China.

Abiel was a very shrewd businessman who had learned early how to play the moneymaking games at both ends of the tea trade. He told his captains to wait when the first tea pickings were offered, and to let the other merchants pay the higher price. Then wait a week or two for the next tea offering at a lower price. All the while knowing that his ships would be among the first to reach the South Street wharves ahead of their rivals even with their head start. To Abiel Low, it was a simple fact of economics. It was also just a matter of keeping track of the new sharp "China Packets" swiftly taking shape in the New York shipyards; particularly that of William Webb, for things were looking up in the China tea trade around that time and the Lows would soon need a new, swift ship if they wanted to stay ahead of their rivals.

Abiel Low soon became as intrigued as his brother and Captain Nat about the model and the possibilities of such a ship. Within a week, work began at the Brown & Bell shipyard. David Brown designed the ship with lots of input from Captain Nat, who, from that point on, became an advisor to the Low's as a marine superintendent.

This ship would be called the Houqua, in honor of the beloved Canton Hong merchant Houqua, who had died the year before, and with whom the Low brothers had traded with in China for many years.

The Tong Merchant Houqua

The Houqua would be built to resemble a vessel of war with high man-of-war bulwarks and eight gun ports on each side. This was not unusual in that time, especially as the opium trade was going on and swift-sailing well-armed merchant ships were in demand for both legitimate and illegitimate purposes. Ships capable of fleeing warships were at a premium. They also had to be well-armed to fend off Chinese pirates in the South China Sea when becalmed, or while running the gauntlet of treacherous reefs, currents, and pirates through the Java Sea. None of the Houqua's design qualities as a fast sailing merchantman were sacrificed for her armaments.

While the Houqua rose in the stocks, the Webb China packet Helena had come romping back from Canton in 90 days on April 4, 1844, and eclipsed Robert Waterman's run that year aboard the Natchez by two days.

The Lows sent off a dispatch to their agents with the next sailing ship bound for Canton asking them to negotiate the sale of the Houqua to the Chinese Government.

Meanwhile, over at the neighboring shipyard of Smith & Dimon, work had already begun on a prototype of a controversial new kind of ship, the Rainbow, but a series of delays had brought progress almost to a standstill.

The controversy and delays had caused considerable anguish to her outspoken designer, John W. Griffiths, but he was steadfast in his beliefs and put up a stoic front to ignore his critics. He was determined to see the Rainbow completed and according to his original scientific theories. They were quite unlike the accepted rules of shipbuilding of his day. Controversy had dogged Griffiths for years, but at last he had been given the opportunity he had sought for so long.

For years, he had espoused to anyone who would listen. Griffiths had lectured about his shipbuilding ideas in February, 1841, at the American Institute in New York City and was ignored. In 1843, this time with a model to display his radical hull and bow ideas, he delivered another lecture to a mostly skeptical audience of merchants and shipbuilders and was greeted with a horselaugh. One of the men who happened to be in the audience this time was the merchant William Aspinwall who was not as skeptical as the others. He knew of Griffiths' admiration of the Ann McKim which his firm now owned and took pride in, for she was still the fastest vessel in the growing China tea trade.

Aspinwall had also bought the old Cotton packet Natchez, and had sent Robert Waterman in command of her around the Horn off to Canton and she had come back from Macao in 78 days, record time, and astonished the South Street shipping community.

1843 was a highly profitable year for Howland and Aspinwall and the shipping firm needed a new, large, fast ship for the China trade. Aspinwall was a man who followed his intuition that had so often been right in the past. Griffiths' enthusiasm had rubbed off on him and Aspinwall was willing to take the gamble. He asked Griffiths to design a fast new tea clipper for Howland & Aspinwall.

But there were hurdles to come. Some of William Aspinwall's partners, notably the elder Howland brothers of the firm, were skeptical after having a look at the plans and were having second thoughts. They had many troubling questions to ask and needed to be reassured before giving their go ahead. Aspinwall decided to bring in Griffiths and William Smith of the Smith & Dimon shipyard to answer their questions. Later that day, they all met in the Howland & Aspinwall boardroom.

The question of the concave elongated bow, her tall masts and narrow freeboard between the deck and waterline troubled the Howlands. Griffiths, in a reassuring way, explained. He said that the sharp hollow bow would be compensated for by the buoyancy of the outward flare at deck level. His straightforward manner in defending his plans proved most convincing. One after another, the partners nodded their approval. At long last John W. Griffiths would get the chance to build the ship of his dreams. She would be called the Rainbow, and would be a large ship of 750 tons register.

But Griffiths still had the wagging tongues of South Street to contend with and they would soon begin to slow him down. Griffiths' idea of a "clipper bow" was the most radical innovation in the evolution of shipbuilding. The Rainbow, by Griffiths reasoning, would slice through the waves like a knife rather than riding up and over the waves like all other ships of the day did with their rounded bows. Griffiths took great delight as he watched her grow upon the stocks. The Rainbow's forward section was elongated and lean with her long sharp bow extending further aft. Her greatest width was at her midsection and her masts were further aft. These three factors were very radical changes in ship design. She was slimmer than the packets of her day, specifically designed to knife through the water. But her critics just couldn't grasp the concept. The Rainbow was indeed a handsome ship, but she frightened them.

Conservative captains and shipwrights said that the Rainbow was "inside out." One big wave, her critics claimed, would send her diving down into the sea.

Griffiths had learned how to ignore the South Street wags and focused his attention on the building of the Rainbow. The work was going slowly as the master shipwrights of Smith & Dimon took their time in working out the new dimensions of this radically different hull to make sure that they did it right.

Then came word that William Aspinwall, in deference to his partners' concerns, was having second thoughts about the masts and rigging and wanted a second learned opinion concerning this. Aspinwall sent the plans for the Rainbow off to some British marine architects for their thoughts about the matter. A number of alterations were proposed by these firms, only too willing to second-guess Griffiths and earn their commissions. Aspinwall received the plans and approvingly sent them on to the Smith & Dimon shipyard. But it was too late, for the mast steps and spars were already finished. Griffiths had no intention of changing his plans anyway and quietly tucked the late-arriving plans away in some dark cabinet never to see the light of day with Aspinwall none the wiser. Aspinwall probably knew all the while that Griffiths would ignore them and just let the matter go. The work would go on in just the way Griffiths had planned.

Busy as he was, Griffiths could not help but pay attention to the building of the Houqua over at the Brown & Bell shipyard. He was acquainted with Captain Nat and had talked ship with him. Captain Nat liked Griffiths' theory about a concave bow but was more partial to his flat-floored bottom as opposed to Griffiths' V-shaped hull. Palmer stuck to his theory and Griffiths his.

Palmer's theories about ship design came from experience and hunches. He had a "try it and see" attitude about the matter. Griffiths' theories were steeped in mathematics.

The ocean would soon enough sort them out, but Griffiths was starting to wonder how his Rainbow would do against the Houqua. How would his clipper bow and V-shaped hull theory of design stand up to this challenge?

How ironic, Griffiths thought, that the Houqua, which incorporated his idea's concerning the clipper bow, was rapidly growing in the stocks, much faster that his Rainbow. The Low brothers wasted no time when they made a decision. The race to the sea was won by the Houqua as she slid down the skids to the cheering New York crowds on May 3, 1844.

The vociferous voice of the New York Herald egged on and captured the building excitement that the American people were feeling for their sailing ships. James Gordon Bennett, a marine writer of the Herald, captured the mood:

One of the prettiest and most rakish looking packet ships ever built in the civilized world is now to be seen at the foot of Jones Lane on the East River. . . .

We never saw a vessel so perfect in all her parts as this new celestial packet. She is about 600 tons in size-as sharp as a cutter- as symmetrical as a yacht-as rakish in her rig as any pirate-and as neat in her deck and cabin arrangements as a lady's boudoir.

Her figure head is a bust of Houqua, and her bows are as sharp as the toes of a pair of Chinese shoes.

Crowds of New Yorkers gathered at the East River to marvel at this latest creation of the maritime world that so captured their imagination. There was the Houqua, anchored off the Brown & Bell shipyard making ready for the China run. Captain Nat directed the fine-tuning of the rigging, while others scurried about paying attention to everything required of a new vessel preparing to put out to sea.

The Houqua was 143 feet long, 32 feet wide, and 17 feet deep. Captain Nat had a one-quarter interest in this unique vessel of war and would deliver her to China for a handsome profit.

On May 31, 1844, six months after the arrival of the Paul Jones, and the meeting of Palmer and the Lows at their South Street counting house, the Houqua set sail for Canton. Captain Nat carried with him the model of the ship hull that he had carved during his last homeward voyage as a gift for the Chinese.

.jpg)

The Houqua

The Houqua made a very fine run down the South Atlantic around the Cape of Good Hope; passing Anjier 72 days out, and 95 days out arrived at Hong Kong according to Low's record. At Canton, the sale of the Houqua did not go through for the Chinese said that the ship was too small to suit their purposes. The Houqua would remain with the Low Brothers. Captain Nat soon came home with a full cargo of tea in the record time of 87 days to Barnegat. There, she took on a pilot and three days later arrived at New York Harbor on March 9, 1845 to much fanfare.

With the launching of the Houqua the previous summer, an increasingly concerned William Aspinwall had ordered the work on the Rainbow to be speeded up to completion. The delays in her construction nagged at him and Aspinwall was certainly not keen on letting the Lows get the jump on him. A year and a half had gone by since Aspinwall had given Griffiths the go ahead to build the Rainbow.

On the cold January Wednesday morning of January 22, 1845, hundreds of people gathered along the East River at the Smith & Dimon Shipyard at the foot of fourth Street; many of them fortified with rum to ward off the icy winds that blew down the river. Off to the side, stood the invited guests, the Aspinwalls, Howlands, Woolseys, and Coits, along with their friends from other merchant houses along South Street. Nearby, the yard workmen gathered with their families.

The enthusiastic crowds turned boisterous and all the contention that had been building up over the past year and a half over the Rainbow's perceived sailing qualities was building. Many of the old salts milling about had come to jeer.

"Which end is the bow?" was often heard, or "She'll never see Sandy Hook!"

There, the Rainbow stood in the stocks, sleek and graceful. A white stripe ran around her hull which accented her lines. Dummy gun ports adorned her sides as a ruse to scare away pirates that her crew might encounter when passing through Sunda Strait on the voyage to Hong Kong. It was obvious to the invited guests that Griffiths had ignored all the suggestions of the European consultants. The Rainbow echoed Griffiths' defiant spirit; her towering concave bow looming over the crowd.

A cannon was fired off at 11 O'clock as workmen knocked the chocks away, and the Rainbow slid down the ways into the river as the crowd cheered on. She soon reached the end of her cables and settled down in the water. Some of the old South Street wags were greatly disappointed when she did not immediately "turn turtle," and dive for the bottom.

Soon, the crowds wandered away and the yard workmen and their families made their way to the molding loft for the customary refreshments of rum punch, cheese, and biscuits. The invited guests soon left in their carriages.

Months earlier, before departing on another run to China in command of the Natchez, Robert Waterman had sought out Aspinwall and asked for command of the Rainbow. Aspinwall replied "She's too small for you." The command had already been given to Captain John Land.

The Rainbow

On February 1, 1845, Captain Land took the Rainbow out past Sandy Hook on her maiden voyage in the dead of winter and the wrong season. Soon, he was racing down the stormy Atlantic putting the Rainbow through her paces, testing her limits, piling on sail, when disaster struck with the losing of all three of her topgallant masts and she almost did drive herself under.

It was all a learning experience for Captain Land as he sailed the rest of the way to Hong Kong against the monsoon in 108 days. Upon arrival, Land decided that the Rainbow was indeed over-sparred and ordered all three masts cut back three feet. The Rainbow then sailed to Whampoa to take on cargo. En route to Whampoa, the Rainbow encountered the ship Monument sailing to New York. After spending 18 days at the Whampoa docks, the Rainbow set sail, again against the monsoon, for New York and still beat the Monument back to New York with a homeward voyage of 102 days. Her precious cargo of tea fetched a handsome profit at auction for Howland and Aspinwall, enough to cover the building costs of the Rainbow and an additional $45,000.

Soon after the Rainbow had sailed on her maiden run, Robert Waterman and the Natchez came home from Canton in an unheard of 78 days; an event that electrified the waterfront. Howland & Aspinwall were elated as they sang the praises of their Captain Waterman, the hero of the day. They began to give serious thought to building a new, large, swift-sailing ship that would capture the China trade and place her in command of their record-smashing captain .

In less than a month, Captain Waterman was off to China on the Natchez, again, chasing after the Houqua and the Rainbow.

William Henry Aspinwall was ready to take another gamble on the talents of John Griffiths. The race between the Houqua and the Rainbow was still on and the results still to be analyzed as to which vessel had the finer sailing qualities. But to the shrewd merchants, it was more a matter of which one held the most cargo that decided the matter. They wanted a flat-floored, U-shaped hull like the Houqua's.

Griffiths finally was faced with the dilemma that he had known was coming. Should he compromise his V-shaped hull theories? Being a man of expedience, he compromised. The new ship would have a fuller-bodied bottom and the Rainbow's sharp bow. She would become his masterpiece; the Sea Witch.

* * * * *

On the 14th of June 1846, the Natchez, under Waterman's command, arrived at the East River docks with a cargo of China tea after an out-of-season passage of 103 days. This was Waterman's last voyage on the old transformed cotton packet and he turned over the Natchez to Captain Land before departing for the Astor Bar to bask awhile in his latest limelight with his peers before a much anticipated reunion with Cordelia in Connecticut.

Captain William H. Hayes had taken over command of the Rainbow from Land and had already set sail on May 18th for Canton via Valpariso. In her first year at sea, the Rainbow had impressed her owners, Howland & Aspinwall. On her second China voyage, she had made it home in 79 days.

Waterman's previous voyage in 1845, in command of the Natchez, had set the record on the China run at 78 days. China was closer than ever before. Now Howland & Aspinwall were more than willing to take another chance and reward him with the command of the Sea Witch.

Her keel was laid under the watchful eye of John W. Griffiths at the Smith & Dimon yard. He still had the South Street wags to contend with, but this time they would not slow him down as the ship grew steadily in the stocks. With Waterman supervising the rigging her owners were betting on Sea Witch to shatter all the records on the China run.

The Sea Witch was larger than the Rainbow by 150 tons and at 170 feet long, 10 feet longer. A carved and gilded Chinese dragon figurehead graced her bow. She had a gleaming black hull with a gold stripe that ran just above the waterline giving her a rakish look. Her mainmast reached over 140 feet; higher than any other ship of her time.

Waterman had a lot of experience with extending booms out from the yards and might have insisted on plenty of spare light sails, but had no influence on the original balanced sail plan. A wide assortment of jibs and flying jibs were hung from the ship's long bowsprit.

Captain Nat dropped by to have a look himself and was reported to have said that the Sea Witch was "likely to prove very swift afloat." Amazed at the tremendous spread of canvas, he added that the Sea Witch "being very heavily sparred, will sail at great expense, to say nothing of the wear and tear." Captain Nat left the Smith & Dimon yard, his thoughts already churning over building another China clipper for the Lows at the Brown & Bell yard to take on the Sea Witch on the China run. He knew that the Lows would not be content to let Howland & Aspinwall take the laurels as well as a lion's share of the profits without a challenge.

As the Sea Witch neared completion, she drew the attention of all of South Street as she had rapidly become the handsomest ship in the harbor, as well as the loftiest, and could spread more canvas than a 74-gun man-of-war.

Her launching on December 8, 1846 drew thousands of spectators. Robert Waterman married Cordelia Sterling in Bridgeport, Connecticut the day before, which postponed the launching for a day. Waterman accompanied his young bride to the launching, where against the clipper bow she smashed a bottle of champagne calling out, "I christen thee Sea Witch; may you always bring your captain and crew safely home." She then burst into tears.

The Sea Witch

The Herald had this to say of the Sea Witch:

The splendid ship Sea Witch, whose peculiar model and sharp bows have for the past few months attracted so much attention, was launched yesterday from the yard of Smith & Dimon, foot of Fourth Street.

She was built for Messrs. Howland & Aspinwall, for the Canton trade, and is to run in connection with the fast sailing ship Rainbow, also owned by the same gentlemen.

The Sea Witch is, for a vessel of her size, the prettiest vessel we have ever seen, and much resembles the model of the steamer Great Britain, only on a smaller scale. She is built of the very best material, and, although presenting such a light appearance, is most strongly constructed. Her figurehead is intended to represent the black dragon-the symbol of the Chinese Empire.

Capt. R. H. Waterman, of the ship Natchez, who, like Capt. Bailey of the Yorkshire, is celebrated for quick passages, is to have command.

Her length is 192 feet over all, 34 feet beam, 19 hold, and 900 tons burthen, making as fine a specimen of New York shipbuilding as we have seen in a long time.

After the launch, Waterman and his new bride left the city for a brief honeymoon in Canada. Howland & Aspinwall was anxious for the Sea Witch to set sail as soon as possible, as was Waterman who returned in ten days to give the vessel a thorough inspection and fine-tune the rigging.

Christmas with his young wife was not to be. On December 23, 1846, Robert Waterman took the Sea Witch on her maiden voyage out into the blustery North Atlantic Ocean. The Sea Witch was christened for the first time by the fierce northwester that splashed against her Chinese dragon figurehead with the open mouth and partly coiled tail as the Sea Witch roared on down the North Atlantic bound for Rio de Janeiro, the Cape of Good Hope, and Canton. The era of the clipper ships had begun.