Contents

- Introduction

- Preface

- Overview

- Relief Valve

- LECTURE 1: Why We Are In The Dark About Money

- LECTURE 2: The Con

- LECTURE 3: The Vatican-Central to the Origins of Money & Power

- LECTURE 4: London The Corporation Origins of Opium Drug Smuggling

- LECTURE 5: U.S. Pirates, Boston Brahmins Opium Drug Smugglers

-

LECTURE 6: The Shady Origins Of The Federal Reserve

- Bank of England - American Federal Reserve Bank

- The Beginning of the Federal Reserve System

- Jekyll Island Federal Reserve

- Federal Reserve Facts

- Federal Reserve Time Line

- Federal Reserve Directors: A Study of Corporate and Banking Influence Published 1976

- Federal Reserve Transparency

- The Logan Act

- Who Owns the Federal Reserve

- The Purpose of the Senate

- 100 Years Later The Fed is A Total Fail

- Lecture 6 Objectives and Discussion Questions

- LECTURE 7: How The Rich Protect Their Money

- LECTURE 8: How To Protect Your Money From The 1% Predators

- LECTURE 9: Final Thoughts

1908-1912: The Stage is Set for a Decentralized Central Bank

USA

1st of all you need to know:

George Walbridge Perkins, Sr. is a direct descendant of the opium drug smuggler Perkins family. The founding families of Skull & Bones included the Russell and Perkins families

Over several generations, however, all these families heavily intemarried and became, in effect, one extended power grouping. considered themselves to be a special elite among the merchant banking and Puritan Pilgrim elite of Yale.

They took the Puritan beliefs of the early New England settlers, that they were "elected by God," and pre-ordained to rule North America.

J. P. Morgan incorporates United States Steel as the first billion-dollar company. He Partners with George Walbridge Perkins, Sr. In 1912 he helped organize Theodore Roosevelt's new Progressive party, becoming its executive secretary. At the convention an anti-trust plank was suddenly dropped, shocking reformers like Gifford Pinchot who saw Roosevelt as a true trust-buster. They blamed Perkins (who was still on the board of U.S. Steel and remained on it until his death.)

McKinley is assassinated and Theodore Roosevelt becomes president.

Jekyll Island and the Federal Reserve

1908-1912: The Stage is Set for a Decentralized Central Bank

- The Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908, passed as an immediate response to the panic of 1907, provided for emergency currency issues during crises. It also established the National Monetary Commission to search for a long-term solution to the nation's banking and financial problems. Under the leadership of Sen. Nelson Aldrich, the commission developed a banker-controlled plan.

- William Jennings Bryan and other progressives fiercely attacked the plan; they wanted a central bank under public, not banker, control. The 1912 election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson killed the Republican Aldrich plan, but the stage was set for the emergence of a decentralized central bank.

1913: The Federal Reserve System is Born

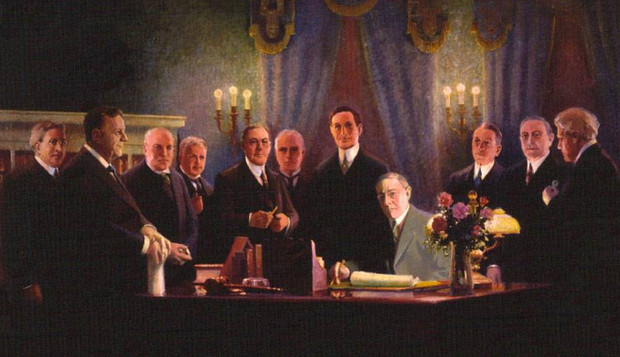

President Woodrow Wilson signing the Federal Reserve Act in 1913 Source Woodrow Wilson Birthplace Foundation painting by Wilbur G. Kurtz Sr.

1912: Woodrow Wilson as Financial Reformer

Though not personally knowledgeable about banking and financial issues,Woodrow Wilson solicited expert advice from Virginia Rep. Carter Glass, soon to become the chairman of the House Committee on Banking and Finance, and from the Committee's expert adviser, H. Parker Willis, formerly a professor of economics at Washington and Lee University. Throughout most of 1912 Glass and Willis labored over a central bank proposal, and by December 1912 they presented Wilson with what would become, with some modifications, the Federal Reserve Act. Woodrow Wilson, 28th president of the United States, taught government at Bryn Mawr College before moving to Princeton University and later serving as governor of New Jersey.

The Secret Meeting That Launched the Federal Reserve: Echoes By Gregory DL Morris Feb 15, 2012

Although it may seem shocking to watch the 112th Congress, there was a time when national leaders were swift and decisive in getting things done. In November 1910, in the space of less than two weeks, a group of government and business leaders fashioned a powerful new financial system that has survived a century, two world wars, a Great Depression and many recessions.

Of course, the Jekyll Island conference, which met that month, was dodgy even by the standards of the Gilded Age: a self-selected handful of plutocrats secretly meeting at a private resort island to draw up a new framework for the nation’s banking system. Add in the gnarly live oaks and dripping Spanish moss of coastal Georgia, and the baronial becomes baroque.

The group's original plan wasn't ratified by Congress, but one very much like it was adopted and became the basis of the Federal Reserve system that remains in place today.

At the time, the Panic of 1907 was still fresh in everyone’s mind. J.P. Morgan had resolved that panic by locking the heads of major banks in his library overnight, and strong-arming them into a deal to provide sufficient liquidity to end the runs on banks and brokerages.

No one was happy with that expediency, and in 1908 Congress passed the Aldrich-Vreeland Act, which formed the National Monetary Commission. Senator Nelson Aldrich, a Rhode Island Republican and sponsor of the act, embarked on a fact-finding mission to Europe, where he met with government ministers and bankers.

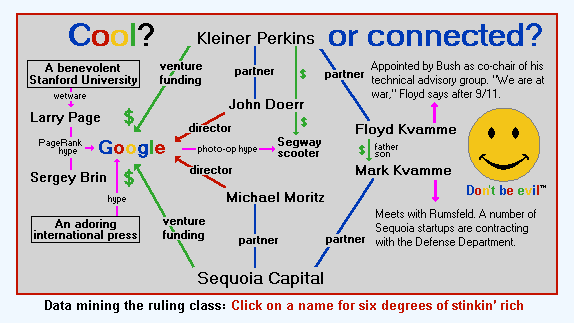

Purpose of the Senate Aldrich,The Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908, Brown Brothers, Harriman, Rockefeller, Morgan, Schwab, Prescott Bush Decentralized Bank

The panic had shown that the existing financial system, founded on government bonds, was brittle and ponderous. But, although voters were eager for a more robust and responsive system, there was no support at the time for a central bank either from the public or from industrialists. Both were suspicious of such government interference.

The Jekyll Island collaborators knew that public reports of their meeting would scupper their plans. The idea of senior officials from the Treasury, Congress, major banks and brokerages (along with one foreign national) slipping off to design a new world order has struck generations of Americans as distasteful at best and undemocratic at worst -- and would have been similarly received at the time. So the meeting of the minds was planned under the ruse of a gentlemen’s duck-hunting expedition.

Aldrich, an archetype of his age, was a personal friend of Morgan, and Aldrich's daughter was married to John D. Rockefeller Jr. He found in the European central banks a useful model. Although the financial system in the U.S. was functional enough to stoke the engines of a growing industrial economy, it was a classic example of the persistence of interim solutions. The models Aldrich found in Europe were more efficient and effective. What he lacked was a way to graft those characteristics onto the American economy without retarding it. Hence the duck hunt.

Aldrich invited men he knew and trusted, or at least men of influence who he felt could work together. They included Abram Piatt Andrew, assistant secretary of the Treasury; Henry P. Davison, a business partner of Morgan's; Charles D. Norton, president of the First National Bank of New York; Benjamin Strong, another Morgan friend and the head of Bankers Trust; Frank A. Vanderlip, president of the National City Bank; and Paul M. Warburg, a partner in Kuhn, Loeb & Co. and a German citizen.

The men made their way to the island by private railway car and ferry.

In Vanderlip, Aldrich had found the tactician to design a functional American central bank. Vanderlip was born a farm boy in Aurora, Illinois, put himself through college, and worked his way up the Chicago financial ladder. He became personal assistant to Treasury Secretary Lyman Gage, and in 1898 made his mark managing loans to the government to finance the Spanish-American War.

As Bertie Charles Forbes related in his 1916 book, "Men Who Are Making America":

Vanderlip knew more about government bonds than any other man living. He knew other banks would like to be relieved of all the red tape incidental to buying and putting up bonds to cover circulation, depositing reserves to cover note issues &c. He began to dictate a circular letter to be sent broadcast to the country’s 4,000 national banks.

That was exactly the kind of perspicacity Aldrich was seeking. The collaborators spent 10 days on Jekyll Island. What emerged was an idea for something called the National Reserve Association, which would act as a central bank, issuing currency and holding member banks’ reserves. While it would handle government debt, it would be a private institution. The U.S. Treasury would have a seat on the board, but would exercise no further oversight.

The reserve association was brought to Congress as the "Aldrich plan," and it got nowhere. There was opposition in both parties, from populist William Jennings Bryan, a Nebraska Democrat, to progressive Robert La Follette, a Wisconsin Republican.

bloomberg.com/news/2012-02-15/the-secret-meeting-that-launched-the-federal-reserve-echoes.html

Woodrow Wilson ran for president opposed to the bankers’ club but committed to financial reform. There followed a blizzard of proposals from every part of the political spectrum. Eventually, Carter Glass, a Virginia Democrat and the chairman of the House banking committee, drafted what would become the Federal Reserve Act with the help of Robert Latham Owen, an Oklahoma Democrat. The act became law at the end of 1913.

Although the Glass-Owen bill was a compromise, the core of the Aldrich plan remained. There were many minor detail changes from the Jekyll Island accords, but the major one was a more prominent role given to the Treasury. (To this day the debate continues as to whether the Fed is truly independent, or should be.) Benjamin Strong, one of the Jekyll Island cohorts, became the first president of the New York Federal Reserve in 1914.

Today, a central bank is the global standard. All 187 members of the International Monetary Fund have them. In November 2010, Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke held a press conference on Jekyll Island to celebrate the centennial of the meeting. Aldrich and his colleagues would have been proud of their accomplishment -- but mortified by the publicity.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York: Data and Indicators http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/data_indicators/ Each of the Federal Reserve Banks has its own outreach efforts, which include public lectures, discussion groups, and a panoply of materials related to financial reports, manufacturing trends, and topics both far-ranging and quite focused. This section of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's website brings together key reports and data sets divided into areas such as Dynamic Data and Maps from the New York Fed, Tools and Indicators from the New York Fed, and Key Data from the New York Fed. The reports here include quarterly trends for consolidated U.S. banking organizations, the indexes of coincident economic indicators, and the Empire Manufacturing Survey. This last one is quite important, as it includes a money survey of manufacturers across the state. Policy makers and other folks will appreciate the regional economic indicators charts and the very important real-time data set for macroeconomists created by the Philadelphia Fed as it includes time series snapshots of major microeconomic variables.

1913: The Federal Reserve System is Born

From December 1912 to December 1913 the Glass-Willis proposal was hotly debated, molded and reshaped. By December 23, 1913, when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act into law, it stood as a classic example of compromise—a decentralized central bank that balanced the competing interests of private banks and populist sentiment.

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) was incorporated in 1921. It is a private group which is headquartered at the corner of Park Avenue and 68th Street in New York City, in a building given to the organization in 1929. The CFR’s founder, Edward Mandell House, had been the chief adviser of President Woodrow Wilson. House was not only Wilson’s most prominent aide, he actually dominated the President. Woodrow Wilson referred to House as "my alter ego" (my other self), and it is totally accurate to say that House, not Wilson, was the most powerful individual in our nation during the Wilson Administration, from 1913 until 1921. That is how the Jesuits controlled even a president of the United States Of America and other countries. The CFR is actually not a part of the American government, it is a separate entity. Among the members of the CFR were Rockefeller, Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon and other American politicians and surprisingly Rev. Father Edmund A. Walsh (founder of the Edmund A. Walsh School Of Foreign Service of Georgetown University in Washington) was also a member of the CFR. The former American President Bill Clinton was also a member of the CFR.

1913:

The Federal Reserve

System is Born

NEXT SEE THE

Federal Reserve Timeline

1913 - 1930

Understanding Charisma and Myth

Charisma and Myth. By Raphael Falco. 2010. London: Continuum. 224 pages. ISBN: 9780826433657 (hard cover).

Reviewed by Daniel Peretti, Indiana University indiana.edu

It is a common enough rhetorical opening to declare that a book explores uncharted territory. Raphael Falco's project in Charisma and Myth is "to explain how certain narratives and certain other forms of discourse are managed charismatically so that the groups sharing and experiencing those discourses are maintained as coherent social units over extended periods of time" (5), an area of intersection which has been unexamined. In Falco's analysis, charisma is transferred from an original, individual authority to a social structure with the aid of a charismatic myth. In other words, the charisma of the individual must be transferred to institutions that can endure beyond the individual, and this is possible through the creation of a myth. Myth thus makes charisma part of a group's quotidian existence and sustains the charismatic movement.

Charisma is the product of group interaction. Here, Falco follows the work of Max Weber. Charisma is what happens when people come together and are stirred toward the same sentiment or action. Furthermore, charisma is symbiotically and dialectically related to myth; the two develop together and support each other. For this to be so, according to Falco, the group's dynamic must exist in a state of mild entropy (he uses the phrase "dissipative structures"), whereby the myths -- which exist in a state of flux as they are reinterpreted by leaders -- are used to support the ongoing authority. This is an important facet of Falco's conception of myth because it informs the examples he uses throughout his book. Early on, he reveals that he places his own study in the context of exploring Malinowski's idea about finding the context of living faith as primary in importance in understanding myth; yet there is little of this in evidence in this book. When he does keep his attention onxt, the book shines: the best examples are his analyses of Milosevic and of the effects that confronting the Japanese population had on the image of Emperor Hirohito after World War II. For Falco, myth becomes an expression not of some sort of truth, but of adherence to charismatic authority. Groups cohere around that authority because of an emotional bond.

Myth has a political context that is of paramount importance to Falco. Folklorists, however, might wish that a more performance-centered perspective had been employed. Performance and charisma seem ideally suited to a joint venture in the understanding of how myth operates in group dynamics. Yet no performance of a myth is ever examined. Likewise, almost no myth is examined, only the abstracted (and barely summarized) myths as used in specific situations, often literary in nature; there are analyses of The Tempest and 1984, for example. These analyses look at the texts themselves rather than at their uses, which is a rather odd inversion of the idea of looking at living myth. These texts, of course, have living contexts: Shakespeare still lives on the stage, and perhaps more importantly, in classrooms, where students are confronted with the texts of the plays in the context of the potentially charismatic teacher.

For Falco, myth is a discursive instrument by which authority can be maintained because of its inherent adaptability. People can alter myths to fit new situations. There is much of value here, including a look at the processes of routinization -- how revolutionary ideals are transformed into a new status quo. Falco is downright folkloristic in his commitment to the constant state of flux in which myth must exist as a living phenomenon. But his choice to devote an entire chapter ("Authority and Archetypes") to the way archetypes -- as formulated by Carl Jung and Mircea Eliade -- can be seen as charismatic, is a curious digression. Archetypes are indeed a potent force in the popular concept of myth (though much less in the academic discourse), but the chapter itself devotes too much space trying to figure out what the term means.

Falco's book, written as it is from the perspective of a literary scholar, relying on sociology and stemming from a desire to expand our conception of an idea broached in anthropology, could use an infusion of folkloristics. When Falco writes that "Anthropologists, scholars of religion, sociologists, even literary critics all acknowledge that myths have a living quality, but few have attempted to define how this living quality functions in social life" (2), folklorists could perhaps be excused for wishing that he had read more books from their field. Folkloristic fieldwork enables folklorists to take it for granted that myth lives in the quotidian habits as well as in the sacred duties of those with whom they work. Falco's reliance on the printed word (he analyzes portions of 1984, The Tempest, and the Bible) blinds him to this fact; the folklorists' attention to performance makes it obvious.

That said, folkloristics could learn from Falco's emphasis on charisma as a function of group dynamics. It is a valid perspective to take to the field. In some sense, we have it already, in the attention paid to "star" performers. In this way, it has already been critiqued as a method of folkloristic research. But it has not been fully integrated, and especially not with attention to myth. Folklorists have studied many situations where myth could be examined in this light -- preaching and political oratory come to mind. To put it this way is essentially to affirm Falco's basic premise and many of his conclusions. Charisma has an intriguing relationship with mythology.